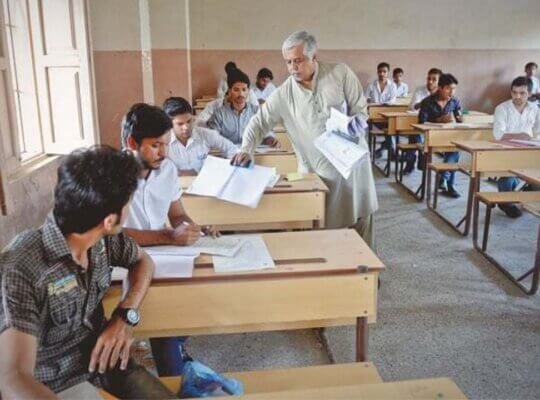

The sound of a ruler striking a desk, the crack of a cane against the flesh, or the sting of a slap on the hand – these are all too familiar sounds for many students in Pakistan and other parts of the world where corporal punishment is still a widely accepted form of discipline in schools.

It’s a controversial practice that has been debated for years, with some arguing that it’s an effective way to maintain order and others insisting that it’s a cruel and outdated method that should be abolished. However, mounting evidence against it begs the question: why are we still using violence to control our children in the classroom? During a recent conversation with a madrasa administrator, I was appalled by his defence of corporal punishment in education.

He claimed that students from affluent families could not handle physical punishment, while those from underprivileged backgrounds needed it to get things done. I was stunned. Is it fair to assume that children from underserved communities are more likely to respond to physical abuse and that it is necessary for their development? It’s an outrageous assertion and completely untrue.

The truth is that corporal punishment is an ineffective disciplinary tool that fails to address the root cause of misbehaviour and often leads to more negative outcomes. Not only can it cause physical harm, but it can also lead to emotional trauma and longterm psychological damage. The issue with corporal punishment in madrasas goes beyond just its use as a disciplinary tool. It’s not uncommon for the management of these institutions to dismiss those who argue against it as part of the “mummy-daddy class”.

They often belittle those who oppose their stance, treating them as ignorant and out of touch with their “teaching techniques”. To make matters worse, these institutions often rely on fabricated traditions to justify physical punishment, leaving people too scared to question their authenticity. One of the most commonly cited justification is that the body parts that have received a teacher’s beating are spared from burning in hellfire. Yet, the interesting thing is that the same teachers who use this justification won’t dare lay a finger on children from affluent families who financially contribute to the madrasa.

Although some madrasas have made progress in eliminating corporal punishment, the issue is not limited to these institutions alone. Reports indicate that many secular schools in Pakistan continue to defy the country’s laws prohibiting physical punishment. Despite the passage of the ‘Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) Prohibition of Corporal Punishment Bill,’ which bans all forms of corporal punishment in formal and informal educational institutions, seminaries, childcare institutions and juvenile rehabilitation centres, there are still teachers who proudly commit this crime. It’s alarming that these individuals can argue in favour of child beating with such ease, and often get away with it too. Society’s soft sentiment towards such behaviour significantly perpetuates this issue. As a result, we hear far too many reports of children enduring brutal beatings at the hands of their teachers. It’s high time for our society to kick the harmful habit of corporal punishment to the curb and usher in a new era of positive discipline.

Scientific research has shown that praising and rewarding children for their good behaviour is a far more effective method for nurturing positive conduct and emotional growth. This also fosters a stronger bond between students and teachers. But to make this vision a reality, we must first debunk the flawed notions that have long upheld the use of physical punishment. We must recognise that every child deserves to be treated with the utmost respect and compassion. Educational institutions must enforce a zero-tolerance policy against any form of physical discipline. And parents need to be properly informed so they don’t fall prey to absurd arguments advocating child beating. We all have a role in creating a world where violence is not used as a tool for discipline and where our children can learn and thrive in safe and nurturing environments.

Meet Najam Soharwardi, a Chevening Scholar and education advocate founded “Off The School” (OTS) to provide formal education to underserved communities.