Asif Qureshi stands on the kerb waving goodbye to his daughter as she sets off for school in the van. On the surface he appears calm and collected, but beneath the surface he’s hiding a deep worry.

He watches as the van disappears down the street, his thoughts turning to the financial burden that the rising petrol prices are placing on his family. “My daughter’s short, 10 to 12-minute drive to school is costing us more than her missionary school fee,” he laments. “And now with this recent hike in petrol prices it’s going to get even worse.”

Asif, a media worker who lives in Karachi’s Martin Road area, knows he’s not alone in his struggle. Many parents face the same difficult reality of paying more for their children’s daily commute to school. But despite his worries, Asif remains steadfast in his determination to provide his daughter with the best education possible.

Meanwhile, several miles away, housewife Khairunnisa Siddiqui navigates the busy streets of Malir Model Colony. She thinks about the long journey ahead for her children. The Cantt area, where their school is located, is a short distance from their home. But with the recent hike in petrol prices, the cost of the daily commute weighs heavily on her mind.

“My son is in grade 5, and my daughter is in grade 9. Together their school fees is Rs10,000, and the van fee is already Rs8,000,” she says, her voice filled with frustration. “How are we supposed to manage this?”

For Khairunnisa the rising cost of petrol is another obstacle in her quest to provide her children with a quality education. But she remains resolute, hoping that the petrol price hike will be a temporary setback, and that relief is just around the corner.

Hope in an unexpected place

In the cramped streets of Nafisabad next to the shanty Teen Hatti town, Amina Naaz makes her way towards Baghdadi Masjid in Martin Quarters. She clutches her seven-year-old son’s hand tightly, her heart heavy with regret and sadness.

Just a few months ago, she was forced to pull him out of school due to her family’s economic hardships. As she walks, she reflects on the daunting reality of Pakistan’s education crisis. With an estimated 22.8 million children between the ages of five and 16 not attending school, according to UNICEF data, the country already has one of the highest rates of out-of-school children in the world.

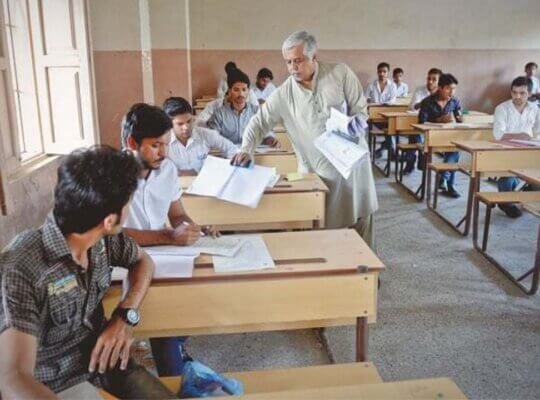

And now with the current wave of inflation, the fear of even more children dropping out is growing. But Amina has found hope in an unexpected place — the mosque. On its premises a not-for-profit organisation called Off The School runs a free education programme for children from underserved communities. As she approaches the mosque, she sees a bustling hub of learning and activity, a far cry from the hopelessness and desperation of just a few months ago.

“I never thought I would be able to send my son back to school,” she says with a quivering voice as tears brim her eyes. “But now, thanks to this programme, he’s learning and growing again. This mosque has given us a chance for a better future.”

Her words are a call to action for religious leaders, the private sector and NGOs to step up and do their part in providing education for the most vulnerable members of society on their doorstep. But as for the government, the mistrust and disillusionment run deep. When this scribe asked a labourer sending his son to a low-fee private school by working two jobs a day, he put it disturbingly: “Sending my son to a government school is equivalent to not sending him to any school at all.”

A matter of dignity and justice

Asif’s phone buzzed on Sunday afternoon with distressing news from his daughter’s school van driver. The monthly commute fee, which was previously Rs3,500, had spiked to a staggering Rs4,000 due to the latest petrol price hike.

Asif expressed his frustration, saying, “My daughter’s monthly school fee is already Rs3,150, and now I have to bear the burden of rising commute costs. It’s a real blow to our finances.”

The rising petrol prices in Pakistan are tearing families apart, crushing their dreams and aspirations for their children’s education. For parents the financial burden is a constant battle, forcing them to make the impossible choice between their children’s education and putting food on the table.

This is a heart-wrenching reality that no parent should have to face. The inability of the state to provide a functional public education sector is not only a failure but also a blatant disregard for the fundamental right to education. It is a breach of trust and a violation of the most basic human right.

The increasing cost of commuting, coupled with the already high cost of education, is putting a stranglehold on the aspirations of millions of families, leaving them hopeless and helpless. It is time for the government to step up and take responsibility for ensuring that every child in Pakistan has access to quality education, regardless of their background or financial situation. It is a matter of basic dignity and justice, and it is our responsibility to fight for it.

This article was originally published in The News International

Meet Najam Soharwardi, a Chevening Scholar and education advocate founded “Off The School” (OTS) to provide formal education to underserved communities.